Ο ιδρυτής της σύγχρονης Ψυχιατρικής (αγγλικό κείμενο)

Πηγή: historytoday.com

Johann Weyer used his compassion and a pioneering approach to mental illness to oppose the witch-craze of early modern Europe.

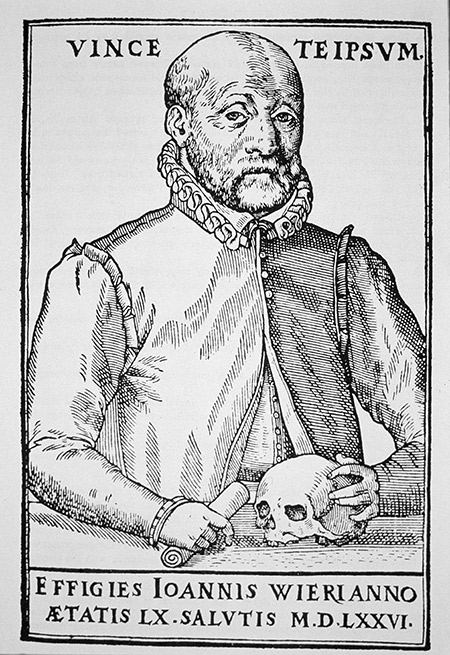

The misunderstanding and persecution of disturbed people was a fact of life in 16th-century Europe and many who suffered were hunted down as witches. Against this injustice there stood one man: Johann Weyer (1515-88), the first physician to specialise in mental illness, or ‘melancholy’ as it was then termed. Weyer (also known as Wier) fought the practice of punishing or killing suspected witches, contending that these ‘melancholics’ were not demonic but mentally ill.

For his insight into the mental turmoil of disturbed persons, Weyer has been credited as the ‘founder of modern psychiatry’ and the year 2015 marks the 500th anniversary of his birth. Though his exact birthdate is unknown, historians say that Weyer was born in 1515 in the town of Grave, in the Dutch province of North Brabant. Scant information is available on his family, but we do know that Weyer had two brothers and that his father was a merchant. We also know something of young Weyer’s educational background. Among his teachers was the controversial philosopher, magician and occultist,Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim, who undoubtedly exposed him to radical ideas.

At age 19 Weyer enrolled at the University of Paris to study medicine. Upon obtaining his medical degree, he returned to his hometown of Grave but eventually relocated to the Dutch city of Arnhem. Here he served as a city physician, in charge of preventing and counteracting infections such as plague and syphilis. He also married and started a family, becoming a father to five children.

Injustice of the Inquisition

Weyer became the personal physician to Duke William V of Julich-Berg-Cleves in 1550, serving in this capacity for three decades. Maintaining the duke’s health was not his only pursuit. He had become fixated on the subjects of witch-hunting and a nascent psychopathology. At this point it is not clear what sparked his interest, though it is true that everyone in that era was aware of the witch-hunts running rampant in both Catholic and Protestant communities. Maybe Weyer could not stand the injustice he saw, which had flourished for hundreds of years and brought misery to those of unsound mind. Organised religion, instead of being a solace for the mentally ill, had become largely their enemy.

The Vatican’s miscomprehension of mental illness had surfaced on December 5th, 1484, when Innocent VIII issued a papal bull on the matter of eccentric people who, ‘unmindful of their own salvation and straying from the Catholic faith, have abandoned themselves to devils’. The pontiff added that, when encountering such people, ‘inquisitors [should] be empowered to proceed to the just correction, imprisonment, and punishment of any persons, without let or hindrance’. A year after this proactive papal bull there appeared a now infamous book, Malleus Maleficarum (Witch’s Hammer), which became a ‘bible’ for some of Europe’s most dogged and ruthless witch-hunters. Robert E. Adler, author of the 2014 study Medical Firsts, writes how Malleus provided moral support to its readers, as well as serving as an instruction manual on how to best execute the stages of arousing suspicion, making an arrest, conducting an interrogation and performing a successful torture and execution.

Responses

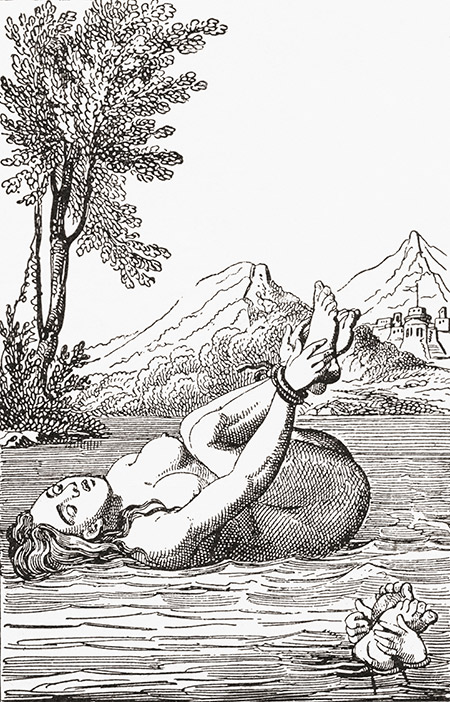

Many of the people arrested confessed to practicing witchcraft. However, most of these confessions were given while the suspect was prostrated on the rack or under the duress of thumbscrews or some other coercion. Weyer argued in his writings that these confessions could be distorted. Not everyone agreed.

The political philosopher Jean Bodin wrote that Weyer ‘should stick to examining urine rather than intruding into the lofty territories of theology and jurisprudence’. Of course, negative publicity was not the only consequence the doctor risked. He was well aware of the perils involved in standing against the practice of witch-hunting. Others could potentially reason that Weyer himself was a demon, looking to secure the survival of his fellow demoniacs. Indeed Bodin felt that the doctor ‘must be a wizard in league with the devil to have shown such sympathy with witches’.

Weyer’s published works had some initial impact; they saw multiple editions in Latin, as well as translations in French and German. The author won the support of some scholars, ecclesiastics and even a group of enlightened judges, who dismissed charges against suspected witches. On the whole, however, the culture of witch-hunting was undeterred. Either Weyer’s medical arguments were insufficient to convince the inquisitors, or the inquisitors didn’t want to be convinced.

No one has any clear idea as to how many lives the witch-craze claimed. Estimates range from 50,000 into the millions. The panic spread to the New World, peaking most notably in the early 1600s in Salem, Massachusetts. It would take time for the persecution to end; for example, the last ‘witch’ in Germany was decapitated only one year before the American Revolution. The memory of witch hunts long remained and its frenzied hysteria could serve as a premonition of the fanatical ideologies that would take hold of Europe in the 20th century.

Weyer, the anti-fanatic, wrote in his magnum opus, De Praestigiis Daemonum (1563), that many of the excoriated witches were in reality ‘melancholics’, whose ‘senses are often distorted’ when the ‘melancholic humour seizes control of the brain and alters the mind’. He added that ‘some of these melancholics think they are dumb animals, and imitate the cries and bodily movements of these animals’. Other melancholics ‘fear death, and yet sometimes they choose death by committing suicide’. Others yet ‘imagine that they are guilty of a crime, and they tremble and shudder when they see anyone approaching them’. Weyer also contended that such psychological states as ‘fascination and enchantment’ could ‘contribute to the belief in witchcraft’. Additionally, social isolation could ‘predispose one to abstruse beliefs’.

Weyer also provided case studies. Among them was one man who ‘was certain he had become a wolf’. Another case involved a man who ‘believed that he was monarch and emperor of the whole world’. A third involved a woman who would ‘linger by night about the tombs in the cemeteries’ for weeks at a time. Sometimes, she would run through the streets vandalising people’s property. Without Weyer’s insight and support such a person would have stood a slim chance against witch-hunters. What else, other than demonic influence, could cause someone to smash her neighbour’s window for no reason?

Legacy

For such a pioneering figure, there is surprisingly little known about Weyer. He left behind no autobiography, nor did any of his contemporaries write anything sizeable on his life or work. In the 1991 edition of Witches, Devils, and Doctors in the Renaissance, George Mora relates that the latter part of Weyer’s life is particularly obscure. One might assume it was less than blissful. Though Weyer had made some initial impact, the grim truth was that the overall persecution of eccentric and disturbed persons was only to intensify. Weyer spent his final years in exile and died following a brief illness, at 73, on February 24th, 1588. Ten years before his death, he had retired from his medical career; the retirement might well have been involuntary.

For centuries, Weyer and his work went largely neglected. Then, in the 1940s, a psychoanalyst and medical historian named Gregory Zilboorg revivified Weyer as a forerunner of modern psychiatry. Today his case studies serve as the progenitor of the current-day psych evaluation, and the Johannes Wier Foundation – a Dutch human rights organisation for health workers – honours a man who breached prejudices that had smouldered for centuries. Where some people saw witchcraft and evil, Weyer saw suffering. And he devoted his talents, compassion and bravery so that others might see it as well.

Ray Cavanaugh is a historian of medieval Ireland and early modern Europe.